The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR)

The genocide in Rwanda 1994

The historic conflicts between the Tutsi and Hutu had been aggravated during Colonial times and had already erupted into violence several times since Independence in 1962. Then, too, it had come to mass murder and displacement. In the early 1990s, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), composed primarily of ethnic Tutsis, was formed in Ugandan exile. The RPF’s aim was to enable refugees to return and to assume control of the Government in Kigali. The RPF’s initial invasions failed, as did efforts to mediate a peace agreement between the parties.

In April 1994 the plane in which Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana was travelling back from peace negotiations was shot down in circumstances that have still not been fully explained. This assassination unleashed a new wave of violence, which quickly escalated into genocide. As the UN’s Commission of Experts later determined, in only 100 days about 800,000 people were systematically murdered, the vast majority of whom were Tutsis or moderate Hutus. More than 2 million people were forced to flee their homes and sought refuge in neighbouring countries.

The international community failed

This catastrophe occurred in front of the world media and in the presence of the United Nations’ UNAMIR mission. At a memorial event 10 years after the genocide, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, who had at the time been responsible for the UN operation, had the following critical and self-critical comments to make about the failure of the United Nations and principal member states to act when they had been so sorely needed:

“The genocide in Rwanda should never, ever have happened. But it did. The international community failed Rwanda, and that must leave us always with a sense of bitter regret and abiding sorrow. If the international community had acted promptly and with determination, it could have stopped most of the killing. But the political will was not there, nor were the troops. […]

The international community is guilty of sins of omission. I myself, as head of the UN’s peacekeeping department at the time, pressed dozens of countries for troops. I believed at that time that I was doing my best. But I realized after the genocide that there was more that I could and should have done to sound the alarm and rally support. This painful memory, along with that of Bosnia and Herzegovina, has influenced much of my thinking, and many of my actions, as Secretary-General. None of us must ever forget, or be allowed to forget, that genocide did take place in Rwanda, or that it was highly organized, or that it was carried out in broad daylight. No one who followed world affairs or watched the news on television, day after sickening day, could deny that they knew a genocide was happening, and that it was happening on an appalling scale. Some brave individuals tried to stop the killing, above all General Romeo Dallaire of Canada, who is here with us today, the force commander of the small UN peacekeeping force that was on the ground at the time. They did all they could. They were entitled to more help.”

A UN Commission of Experts revealed the extent of the catastrophe in a report at the end of October 1994. The genocide in Rwanda gave the countries concerned and the United Nations cause for thought. A series of reflections, proposals and measures was the result. One of these was the report on “The Responsibility to Protect”, submitted after several years of consultations by the working group headed by former Canadian Foreign Minister, Lloyd Axworthy. The international community also wanted to take steps to bring to justice at least the main persons bearing responsibility for the genocide. The Security Council thus established an ad-hoc tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in Arusha, Tanzania, modelled on the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), in order to investigate the horrors of the genocide and to hold those responsible to account without regard to their position.

The ICTR charts new legal terrain

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda has many similarities with the Yugoslavia Tribunal. Like the ICTY, the Rwandan tribunal, which has its seat in Arusha, Tanzania, is an ad-hoc tribunal with limited temporal and geographic jurisdiction established under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. It commenced its work in late 1995 and has the task of investigating the crimes committed in Rwanda in 1994 and bringing the prime perpetrators to justice. But the ICTR has some important features that distinguishes it from the ICTY:

The ICTR is the first court to have delivered a judgment that relied on the UN Genocide Convention of 1948 (in the Akayesu case). Jean Kambanda, Prime Minister of Rwanda from April through July 1994 during the genocide, is the first head of state in the world to plead guilty to the crime of genocide. The Tribunal has very clearly categorized sexual violence as part of genocide. The persons accused and convicted include politicians and soldiers as well as businessmen, priests, doctors and media people who were involved in the genocide. The role of the media, whose hate speech made such large-scale genocide possible in such a short period of time, has been highlighted. For the first time since the Nuremberg trial, incitement to genocide has been condemned as a crime against international law.

The ICTR and the national courts

Rwanda was home to millions of victims, but also to countless perpetrators. However, the ICTR only has the capacity to try a limited number of those who bear a particularly serious responsibility for the crimes committed. It is therefore vital that justice is also meted out at national level. Relations between Rwanda and the ICTR were occasionally strained. Some of the ICTR’s judgments were considered too lenient by those in Rwanda. It is nonetheless important that the crimes perpetrated as part of the Rwandan genocide are also prosecuted as international crimes. The ICTR has set new standards in the region for fair trials under the rule of law. Thus, the death penalty, which is excluded in all international courts, has also been abolished in Rwanda.

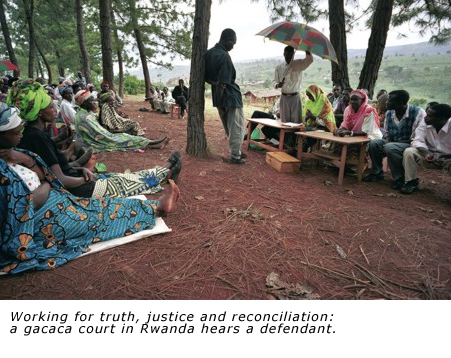

In addition to the ordinary courts, “gacaca jurisdictions” have been established. These are people‘s courts with lay judges, derived from traditional concepts of community justice. The aim of these gacaca courts is not only to judge alleged offenders, but also to advance the process of reconciliation.